Friedrich Nietzsche’s mortuary mask and cover of the original edition of The will to power

We have entered a new geopolitical era marked by cruelty and pettiness and by the recourse to war with spurious interests. Among the major powers there is neither the will for peace nor the true will for power – translated as strategic intelligence in favor of humanity.

_____________________________________________________________

At the beginning of 2024, I spent a few days in the delightful village of Sils Maria, in the Swiss Alps, next to St. Moritz and south of Davos. Sheltered from the snow, I was able to visit the house of Friedrich Nietzsche, where the enfant terrible of Western philosophy used to spend some summer seasons. In reality, it was a boarding house where his meagre resources allowed him to rent a room. Today, it is a museum that houses the memorabilia of the writer. Later, several notorious figures of the early 20th century vacationed in the village, including Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, and the unfortunate Anne Frank in her childhood. I bought an English copy of The Twilight of the Idols (Götzen-Dämmerung) and re-readit, many years after I had looked at the booklet (Spanish version) in the distant Buenos Aires of my youth.

The paragraphs of The Twilight are short and punchy. Even more so the aphorisms. Both frequently slide into reproach. For Nietzsche, war was the realm where the human being reaches its best and most genuine expression. Thus, Nietzsche places himself squarely in the tradition that goes back to archaic Greece in our civilization (the work of Homer, in particular The Iliad). There would be no truer form of life than death given and received by warriors. Face to face, hand-to-hand, they are heroes and demigods – all male, since women participate in combat only as booty or as goddesses.

The warrior is the ultimate libertarian: selfish and sovereign, he risks his life, which he both exalts it and despises. But Nietzsche reserves a greater contempt—another kind of contempt—for the self-righteous, the pacifist, the humanist of good intentions, of ‘love of neighbor,’ which he sums up in the figure of the “Christian.” In short, it is an authentic being who seeks the fight – the terrible hand-to-hand of the fight to the death. The corollary of this thought is this: genuine peace is not in surrender or compromise, but in the reciprocal gift of great warriors. Only those who have distinguished themselves in war are capable of making peace. For Nietzsche, true peace arises from a decision of the war heroes.

In another pamphlet entitled The Wanderer and His Shadow, the philosopher glimpses the possibility of sustainable and lasting peace, which I have quoted in a previous article and which says (I repeat):

“And perhaps a great day will come when a people distinguished by wars and victories, by the highest development of military discipline and intelligence, and accustomed to make the greatest sacrifices for these things, will spontaneously exclaim, ‘We break the sword,’ and dismantle to its very foundations its military organization. Disarm yourself when you have been the most armed from a height of feeling, that is the means to real peace, which must always be based on a peace of attitude; while the so-called armed peace, as it exists today in all countries, is the root of the attitude that distrusts itself and its neighbor, and partly out of hatred, partly out of fear, does not lay down its arms. It is better to perish than to hate and fear, and doubly better to perish than to be hated and feared: this must one day also be the supreme maxim of every single state society!”

This heroic version of war and peace in Nietzsche’s work seems utopian to me today more than ever. The technological and organizational evolution of modern societies has made war not a heroic combat (or even “classical” combat in Clausewitz’s sense) but a dirty war. I will cite just two facts that seem to me to confirm the filth of war. One is the preponderance of asymmetric warfare, which is not fighting between noble warriors inNietzsche’s way but between invaders and resisters, where “anything goes” and there is no distinction between the righteous and the sinners, combatants and non-combatants, civilians and soldiers, near and distant, culprits and innocents. Whoever kills with a drone can do it thousands of miles away, in front of a screen, drinking coffee. On the ground, in front of a boy carrying a bomb, a soldier faces this dilemma: if he does not kill him, he is an imbecile, and if he kills him, he is a monster.

The other illustrative figure is the proportion of civilian and military casualties in recent wars compared to past wars. In Clausewitz’s time (classical warfare), the proportion was: 9 out of 10 victims were soldiers, and 1 civilian. Today, the proportion is exactly the reverse: out of every 10 war victims, 9 are civilians.[1] These are ongoing “hot” wars, civil wars, or inter-state wars of a regional and limited nature. As for a generalized nuclear war, so far it has not broken out because of the fear caused by the possibility of the total destruction of life on the planet. This is the spurious “armed peace” despised by Nietzsche.

If socio-technical evolution has relegated the “noble war” extolled by Nietzsche to a museum, the same has happened with his concept of the “will to power.” Today, those who promote war or incite it do not do so as a sovereign exercise of the famous Der Wille zur Macht (The Will to Power) but by petty appetites or to avoid being driven out of a usurped or illegitimate “power.” The will in Nietzsche, on the other hand, is firmness of purpose, solidity of plans to be carried forward, courage in the face of difficulties.

Everything great is the result of effort and renunciation. Those who have an educated will are freer and can lead their lives wherever they want. Perhaps, it is appropriate to translate the concept as “desire to excel”. The best examples are not to be found in the political sphere, where a vulgar “lust of domination” prevails (which is not Der Wille zur Macht, theWill to Power) but in the artistic sphere, in creative energy – the powerful will of a Michelangelo, or a Bach, or a Shostakovich. Such overcoming energy is also found in some charismatic and visionary leaders and even in some empire-makers, from Alexander to Bonaparte, but they are a minority among autocrats. In these rare examples, violence and war are part of the creative energy, not a resource to be resorted to by default to satisfy petty interests.

We will not find examples of greatness today in the geopolitical area. On the contrary, in the upper echelons a mediocre baseness is multiplied. As I contemplate them, I am reminded of the much-mentioned and comical insult devised by Dr. Samuel Johnson (and repeated by Jorge Luis Borges) between two supposed gentlemen from another century: “Sir, I must warn you that your wife, under the pretext of running a brothel, smuggles stolen goods.” Behind the grandiloquent phrases (or scandalous ones as in the cited example) are hidden banal or sordid appetites. Behind them hide those who earn large or small sums, and some portion of worldly power. They are not heroes, but thieves or bribers. Today, even high-sounding phrases have worn out and have led to an exchange of insults with devalued concepts: among others, “human rights,” “terrorist,” and “genocide.” They are often mere loincloths. Those words have lost their value, just like ordinary currency that loses value in war zones.[2]

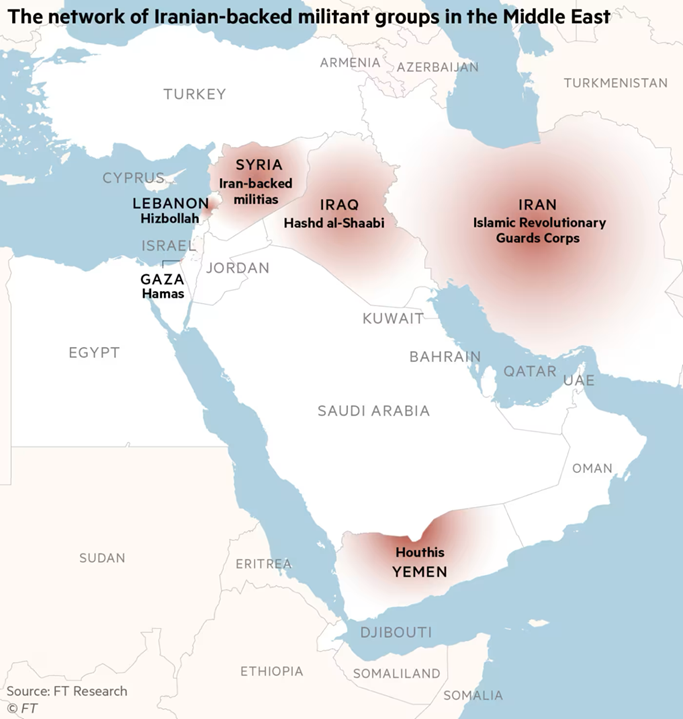

Who wants war? In the U.S., a country that is no longer “indispensable” but remains “inevitable,” the military-industrial complex is the main beneficiary of wars where others die, and the Pentagon sells a bundle. In the Middle East, leaders on two sides (Israel/Hamas) provoke and then prolong a bloody war to stay in power. The same thing is happening in Iran and its satellites. China also incites and provides weapons while pretending to abstain. In Russia, a corrupt regime is counting on the war (for now in Ukraine) to sustain itself: murderous inside and outside its borders, it kills in retail and wholesale. War is the troubled river where unscrupulous fishermen hope to make a profit. Only international organizations that are reduced to a painful irrelevance are fighting for peace.

In my opinion, we are about to enter a new era of geopolitics, or of world history: a reactionary era that is shown in armed conflicts everywhere and in the return of autocracy in many countries.

With the French Revolution, 232 years ago, the world entered a new historical epoch, marked by popular sovereignty, the concept that Rousseau had advanced and was a favorite of the founders of new republics on the American continent. In 1792, the armies of the European powers opposed to the revolution were defeated in a battle in the town of Valmy, quite close to Paris. With that battle, the doors were opened to the expansion of revolutionary ideas throughout the continent, imposed by arms. On the night of the defeat, on September 20, the great German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who accompanied them, pronounced the famous sentence: “Here, and today, begins a new epoch in Universal History, and you can always say that you were present.”

Less precisely, in these days of wars East and West, another new epoch also begins, which we receive with less exaltation than Goethe and with much greater apprehension: the return to cruelty on the part of countries and empires, new and arrogant or old and tottering, the return to despotic arbitrariness instead of debate and democratic alternation, a way of doing politics that many centuries ago was common practice in the Roman Empire[3]. Trump, Putin, Xi, Modi, Orban, the ayatollahs, and so many other leaders use democracy (most of which has been captured and distorted through populism) to install autocracies. Then, they use war or murder to stay in power. It is a great restoration, and it is mean. In this setback, those who survive the coming destruction will be able to say that they were present at the birth of this new dark age. Let’s hope it does not last long and will not cause irreparable damage to the planet.

In the meantime, how could the war in the Middle East extend into a major regional war or a global war (if connected to the one in Ukraine)? The key lies in the behavior of Israel and Iran with their outbursts and the coming political chaos in the US. Just look at the map of the so-called “axis of resistance”[4] to draw a serious conclusion:

If the Western world (the US and Europe[5]) comes to define Iran as the epicenter of all conflicts in the region – which is already happening – it will align itself with the interests of the current government of Israel in a major attack on the Persian country. What will come next, nobody knows. But things are like this: all state or para-state powers are on the edge of a precipice, with some willing to step forward. Strategic vision is scarce; the will for peace: none. It is the geopolitical version of the “tragedy of the commons.” Each actor plays for himself, and the bewildered set glimpses destruction.

[1] United Nations Report, 25 May 2022 https://press.un.org/en/2022/sc14904.doc.htm For a longer historical overview, see https://www.jstor.org/stable/23609808 For the evolution of the ratio in the 20th century see https://militaryhistory.fandom.com/wiki/Civilian_casualty_ratio

[2] Even the well-argued accusation of genocide against Israel by the Republic of South Africa loses value in the face of that republic’s notorious silence in the face of massacres committed by other states on its own continent. Besides, the president of South Africa is using the war in the Middle East to distract from his domestic problems and regain some popularity. To appreciate the sordidness of power in a power, I recommend Giuliano Da Empoli’s book, El mago del Krelim (The Wizard of the Kremlin), Barcelona: Seix Barral, 2022.

[3] See the great study by Mary Beard, EMPEROR OF ROME: Ruling the Ancient Roman World, NY: Norton, 2023, in particular, the epilogue.

[4] The expression refers to an anti-Israel security treaty between Iran, Syria, and the Lebanese Shiite group Hezbollah, which clashed with Israel in 2006, with the backing of Iranians and Syrians. The alliance also includes Hamas and some Palestinian guerrilla groups. Venezuela is part of the Axis of Resistance against Israel and the United States. (Wikipedia).

[5] The European Union faces an uncomfortable dilemma: it is very close to the US, which uses it but also despises it. In gaucho expression, it’s like “a dog on the bocce ball court.”

If you liked this text, you can subscribe by filling out the form that appears on this page to receive once a month a brief summary of the English Edition of Opinion Sur

Opinion Sur

Opinion Sur