American old political bipartisanship is broken. The social costs of various decades of globalized and concentrating neoliberalism are now evident. The two main parties have become polarized and have cracked, between a populist and semi-fascist right and a center that loses strength every day while facing a new youth mobilization on the left.

For a long time it has become banal to talk about revolution. We watch TV adds that announce the introduction of a new “revolutionary” product, even while referring just to a simple egg beater. There are “revolutionary” designs in the vehicle fleet, and in the fashion field there is a “permanent revolution.” In summary, “revolution” is a degraded word that neither excites nor scares anybody.

However, to quote Galileo: Eppur si muove. Whether we like it or not, there are changes and changes are important in the three dimensions that used to define the term when revolution was spoken of seriously: change in the relations of production, change in the social structure, and change in the political system.

In this article I refer to important changes that are still taking place in the American political field, not just for anthropological interest in a country that in several aspects, good and bad, is exceptional, but rather because of three geopolitical compelling reasons.

In the first place, the internal politics of the US have a global and immediate impact, especially at a time when the international power equilibrium is in a process of reconfiguration. Apparently the world’s fate is affected by what a 7% of the world population does or does not do. The world is interested in American presidential elections, though the majority of the world cannot vote in those elections.

In the second place, changes in US politics are part of the parallel phenomena in the internal politics of other countries, particularly the European nations.

And third, the globalization process that affects every country is out of control for any and all countries.

My first observation is that the bipartisan system is broken. The consensus of the “imperial classic” era, eloquently expressed by John F. Kennedy in his inaugural speech where he pointed out that the differences between Democrats and Republicans were in the means but not in their goals, and had to do with the orientation details of their public policies (one more egalitarian and pro civil rights than the other), no longer exists. It has been replaced by what we could call the Republican secession that began in 1982 with Ronald Reagan’s election and nowadays goes far beyond the positions of the Reaganite right. Let’s review its evolution.

The Republican party of Dwight Eisenhower today is unrecognizable. General Eisenhower, the former commander in chief of the victorious allied forces in WWII, represented the triumph of “modern republicanism:” a center-right party that had made peace with progressive reforms of Franklin D. Roosevelt, to which it added the abandonment of the old isolationist position in favor of an anti-communist internationalism. In sum, it was about consolidating the huge material advantage of postwar, while keeping economic growth running and stopping the advancement of an alternative model of economy and society promoted by the Soviet Union and its socialist allies. On the one hand, Democrats were committed to maintaining a global counter revolutionary position and, the on the other hand, Republicans endorsed a global and Keynesian economic policy.

This 20-year-long bipartisan consensus was broken with the Vietnam War. There was no longer unity in the international order during the Cold War. On the internal front, the stagflation destroyed the Keynesian consensus. And, on top of that, serious divisions within civil society broke out with anti-establishment, juvenile, pacifist, feminist, racial and minority movements. Civil society moved from consensus to polarization and from ideological unity to cultural war. This situation lasted a decade, characterized by internal dissent and strategic paralysis. This double contingency (social fight and economic stagnation) paved the way for Ronald Reagan’s triumph. He offered a right-wing exit from the impasse.

The so called “Reagan revolution” was in reality the fusion of an economic model of concentrated growth (supply side economics), with an aggressive and militarist twist in the international field, destined to “break” the already shaky Soviet Union, and a social conservatism that exalted the virtues of “God, nation, and home.” This reactionary “revolution” lasted until Barak Obama’s election as president (Clinton’s progressivism was cosmetic and did not alter the basic parameters) after a Republican administration (George W. Bush) that was pretentious and disastrous, ending in a military misadventure in the Middle East and a world financial crisis of colossal proportions.

But Reagan’s ideology still dominated the thinking of the Republican elite until the beginning of the nomination process in view of the 2016 presidential election. It was a period when Republicans kept control of Congress and efficiently torpedoed almost every progressive initiative presented by the executive. On his side, president Obama at the same time pretended to manage the neoliberal crisis inherited from the previous administration and return to Kennedy’s optimism. He could not do it, except in some details. He was elected and reelected by popular vote but he did not overcome the power “tie.” His administration was characterized by a double paralysis: domestic and international. In the meantime, globalization transformed the social basis of parties.

During the 80s, Reagan’s Republican “revolution” was possible due to a change in attitude by the white working class (once the hard core of Roosevelt’s Democratic Party) that swung to the right and voted for the Republican Party. The realignment of this social class to the right was more a cultural reaction than an economic one, as it felt attacked by anti-system movements of racial demands, civil-rights, and non-traditional social and sexual affirmative action demands. The economic issue was secondary to them, but not for the elite that had a free rein to promote the great neoliberal reform urbi et orbi: the undoing of previous social conquests, a global free market, and a legally ambiguous policy on immigration. The illusion of prosperity was supported by a strong private indebtedness in a speculative service economy that replaced the much older industrial economy.

Everything changed with the irruption of what came to be called the Great Recession—a financial crisis of epic proportions with an epicenter in Wall Street that shook the world in 2008. The curious web that linked the global elite with the national-racial working class began to fray.

Workers started blaming big corporations for taking away jobs as they move to poor countries or “emergent markets” looking for a cheap labor force. The complaint was based on the loss of millions of jobs. Furthermore, they started to blame immigrants for “unfair competition” in the labor market—particularly their disposition to take low-income and precarious jobs, the “blind eye” of local employers regarding the flow of illegal aliens. Therefore, the most exploited people were accused of abusing the system.

General economic uncertainty made integrated workers refuse their previous support for old republican initiatives of reducing social spending, which now turned into the last defense line for a downward moving class. Having a sector of the victims of a global process blame another sector, distorts social struggle in favor of elites though at the same time bringing them some unpleasant surprises. Furthermore, the white working class that in previous times supported the armed intervention in Vietnam has turned against the armed intervention in the Middle East, with a war as long as it is disastrous, in which this social stratum was used as cannon fodder. The voluntary engagement that followed the draft was concentrated in popular class youth. They saw in the armed forces an economic and social shelter at times of reactionary adjustments, but they had to bear the burden of repeated military and deadly campaigns.

It is through that crack that right-wing populist movements, with a long and sad history in the contemporary world, moved in: an amalgam of social resentment, anti elite-capitalism, racism, xenophobia, chauvinism, nativism and moral indignation. If we add to these ingredients that catalyst of a sense of insecurity promoted by terrorism and increased by the media, there is a surge in demand for a decisive, authoritarian, and charismatic external political action against the normal system.

There is never a lack of candidates to occupy the role of “savior,” as charisma is not the particular property of a person that builds a situation but rather the result of a situation and social expectation that afterwards is occupied by any “available” person. For a long time, role theory in sociology disentangled the mystery of seduction and charismatic leadership. In particular, the analysis of the political predisposition of the small middle class is well established since the publication in 1938 in Denmark of the essay Moral Indignation and Middle Class Psychology by the sociologist Svend Ranulf (during the heyday of Italian fascism and the German national-socialism). It was a historic and comparative analysis of groups and individuals that show a tendency or habitus (independent from the material of class interest) for punishing other chosen groups as escape goats to reinforce their own identity and feel less isolated. Ranulf placed these groups with tendencies towards free victimization in the medium-lower layers either within downward as upward mobility.

There are always political leaders willing to capitalize this tendency and mobilize those groups—leaders such as Savonarola, Cola Di Rienzo, or Benito Mussolini in Italy, Adolf Hitler in Germany, Joseph McCarthy in United States, Pierre Poujade in France, and many more. Ranulf’s analysis received empirical confirmation in several more refined studies that followed him to this day.

In United States no fascist candidate managed to gain power –until now.. There was an attempt by Louisiana governor Huey Long (who, together with Benito Mussolini, inspired then colonel Peron), but he was assassinated before he could organize a national campaign.

During the Korean War, General Douglas MacArthur rebelled against the president but was summarily dismissed by Truman, despite which he made a triumphant celebration –Roman style– in the American Congress and New York streets. At the beginning of the Cold War, Senator Joseph McCarthy organized a campaign of political persecution and witch-hunts against alleged Communist sympathizers that grew until the top commanders of the army stopped his campaign and produced his eventual destitution (he was forced to resign).

American democracy went through all these mishaps and passed with flying colors, due in part to a good constitutional design of the division of powers. However, there always existed in the collective imagination (with a little help from Hollywood) the ghost of a dictator, not of military origin but from the civil power elite (finance, media, industry, or real estate). To this day, such character has existed only in fiction. There are two very good examples. In literature, there is a satiric novel called It Could Not Happen by Sinclair Lewis (1935) and in the film industry there is Orson Wells’ great movie titled Citizen Kane (1941).

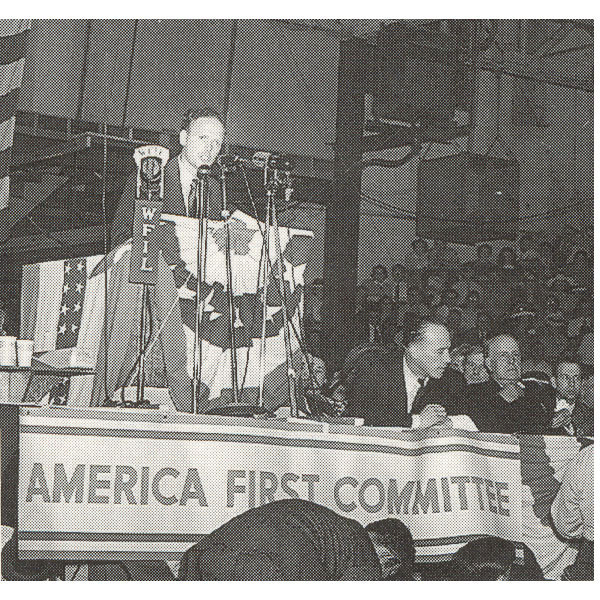

In 2016, such a character has made an entrance in the person of Donald Trump. Trump proposes to reverse Ronald Reagan’s formula. In opposition to the majority of his party by adoption (the Republican Party), Trump is not a social conservative, neither by his ideology nor by his biography. His tolerance for same-sex marriage combines with the cheap machismo of a locker-room. He is agnostic in terms of religion and did not mind challenging the Pope. He is not against abortion now but he was before, or vice versa. He is chauvinist and nationalistic. He rejects alliances with European countries, which he distrusts, and he promises a “steady hand” against former communists (Russia and China) but he does not hide his attraction toward the authoritarianism of Vladimir Putin. Many of his mottos (“Make America Great Again,” or “America First”) echo older ones, like that of Charles Lindbergh, an admirer of the German Fuehrer.

In terms of economics, Trump proclaims autarky and favors keeping social and medical assistance to people. He is not opposed to state intervention, as long as it is of his liking. Regarding the division of powers, he aims at having a strong executive and he prefers the other two to be submissive. To the surprise of his alleged colleagues, the most popular candidate of the Republican Party is mercantilist and isolationist. Whether he wins the presidency or not, Trump has signed the death certificate of his own party.

In front of Donald Trump stands the well-known and controversial figure of Mrs. Hillary Clinton. She will win the primaries of her party in a symmetric and opposed path to that of Mr. Trump’s among the Republicans. Clinton represents the establishment in its Democratic version, i.e., free trade, imperialism in foreign policy, and elite capitalism (especially financial) of Wall Street. In social matters, she is definitely lefty liberal, as she favors minority rights, civil guaranties, and social justice for all women in terms of salaries and jobs. But with this double attitude, and with a heavy load in strategic mistakes regarding foreign policy (as her suppositions regarding Iraq, Libya, and Israel) and a clear lack of sincerity in her positions, she does not convince younger sectors of the Democratic Party, to whom she irritates for her quasi monarchic attitude of someone who believes she has a birthright to the first seat of the nation. The huge enthusiasm for the candidacy of her rival in the primaries, Senator Bernie Sanders, was not able to win over the oligarchic apparatus that is supporting Hillary Clinton.

In this way, November 2016 elections will offer two candidates whom most of the voters distrust—the populist right against the oligarchic apparatus—in two severely divided parties. That is a sure recipe for great social conflict in the future.

The American bipartisan system is broken. This political earthquake with epicenter in Washington will be felt in every corner of the globe. Hillary Clinton represents what is well-known—with all its defects. Donald Trump represents the unknown—with all its dangers. The Democratic Party has become a bastion of the establishment, and the Republican Party the bastion of authoritarian resentment of the establishment. In a cycle that mimics the generational cycle of Garcia Marquez’s novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, American conservatism, after decades of proclaiming hatred for the government, promoting a barely disguised racism, showing disdain for minorities and hailing armed individualism, finally has given birth to a child with the tail of a pig.

Opinion Sur

Opinion Sur